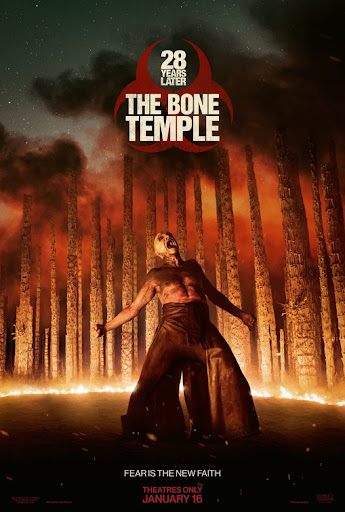

28 Years Later: The Bone Temple

2026

Directors: Nia DaCosta

Starring: Ralph Fiennes, Jack O’Connell, Alfie Williams, Erin Kellyman, and more.

As Spike is inducted into Jimmy Crystal’s gang on the mainland, Dr. Kelson makes a discovery that could alter the world.

This film occurs in two arenas. There’s Spike literally fighting to survive in the world of Sir Lord Jimmy Crystal (Jack O’Connell). That situation is a lot on its own. In the first scene of the first film, we saw a young eight-year-old Jimmy in a room with a lot of other children watching The Teletubbies which was a huge kids’ show in that era. When the house is overrun by the infected, Jimmy barely makes it out to find his father in the church. His father, the pastor, is telling him it’s the end of time and welcomes the infected who crash through the church to come get him. Jimmy manages to hide, but it all had an impact on the boy. As a man, he’s the head of his own cult of Jimmies. He calls his chosen “the fingers.” What’s really scary is that they all wear colorful jumpsuits (Teletubbies), wear long blond wigs, and fight the infected like ninjas. Oh, did I mention that they torture and kill other humans/non-infected in the name of Satan? Yeah. That’s where our brave little hero has landed.

The other arena is the bone temple and Dr. Kelson (played spectacularly by Ralph Fiennes). He still gets visits from the alpha infected, who he calls Samson. Samson has become accustomed to the drugs Kelson uses to subdue him until finally either Kelson has made a breakthrough or the infected is now an addict. I won’t say more there but an odd friendship develops here. Dr. Kelson’s time with Samson has him thinking there just might be a way to cure the infected after all. Is he right? Their relationship is fragile, awkward, and deeply human in a world that has forgotten how to be.

When the two arenas collide, you get one holy hallelujah of an ending that any horror film fan would love as much as I did.

Twenty-four years after 28 Days Later (2002) accidentally became a cornerstone of modern horror, 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple arrives as the strangest, gutsiest evolution of the franchise. It doesn’t look like Danny Boyle’s films. It doesn’t follow the zombie movie rules at all. And that’s why it works. This is the second entry in a follow-up trilogy that truly interrogates what comes after societal collapse on many different levels.

That ambition of this entry is the film’s first complication. The previous film felt more like a soft reboot, introducing new faces and ideas but ending before it could fully land them. I get why some didn’t like the first movie. This one picks up immediately where that film left off, and then stops just as abruptly. There’s no traditional beginning, no clean resolution. What you get instead is a self-contained descent, but it that doesn’t actually need a future payoff to justify itself.

The second issue is more visceral: jump scares. DaCosta leans on them too often. One or two would have been fine. Beyond that, they feel unnecessary in a film that’s otherwise so skilled at cultivating dread through atmosphere, implication, and moral rot. When this movie is quiet, it’s terrifying. When it jolts, it occasionally undercuts its own power. But that’s a minor complaint.

Alex Garland’s writing, often accused of overreaching, is unusually disciplined here. The writing is lean, brutal, and precise. Where earlier scripts sprawled, The Bone Temple focuses. The film’s thematic spine is clear: when systems collapse, people don’t innovate, they retreat. The Jimmies cling to corrupted pop icons. Kelson clings to music (Duran Duran), memory, and ritual. Everyone is searching for a version of the past where things made sense.

DaCosta translates this idea into pure cinematic unease. Her direction is confident and restrained, and she understands that horror doesn’t require spectacle, just inevitability. Violence isn’t shocking here because it’s loud, it’s shocking because it’s normalized. Her control over tone is damn near perfect, and it elevates Garland’s ideas into something haunting and cohesive.

Though Alfie Williams’s Spike anchors the story, this is ultimately Fiennes’ film. Kelson is opaque, melancholy, and quietly compassionate. Fiennes plays him without irony, making kindness feel radical in a world defined by survival. His performance suggests that goodness isn’t extinct, but endangered.

The finale doesn’t aim for catharsis as much as recognition. Like Romero’s best work, it reframes the entire series as a study of societal decay rather than infection. Fear becomes geography. Faith becomes infrastructure. Monsters don’t just rise, they remember.

I admired 28 Years Later. I love The Bone Temple. It’s unsettling, intelligent, and deeply uncomfortable in the best way.

Isy